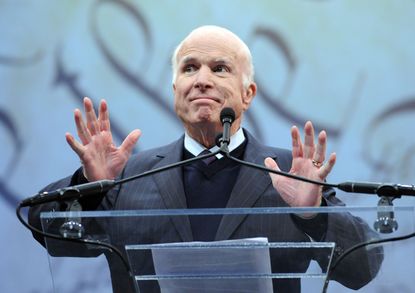

John McCain's abstract America

McCain appeals to abstractions as much to avoid debate as to engage in it

John McCain is being applauded for delivering a fiery speech denouncing "half-baked, spurious nationalism" as he accepted the National Constitution Center Liberty Medal in Philadelphia on Monday.

The cheers are understandable. Whatever your views of his Senate voting record, McCain is an American hero who is justly celebrated for his sacrifices in Vietnam. He is showing grace and resilience in fighting a terrible illness. And yes, his targets are clearly the likes of President Trump and former White House strategist Stephen Bannon.

Nevertheless, there is much about McCain's remarks that is wrong or at least incomplete. And his errors are precisely what is fanning the flames of the populist and nationalist backlash he now denounces to such great fanfare.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

"We live in a land made of ideals, not blood and soil," McCain declared. This is something the man who beat McCain in the 2008 presidential race might describe as as "false choice."

The United States has had an ideological component to it since the founding of the republic, and we have never been an ethnostate in the sense of, say, Japan. But every country that exists is also a place, a homeland to real flesh-and-blood people whose lives can't be defined by a political tract or quantified in our national GDP.

Many of the brave men who fought alongside McCain in Vietnam believed they were fighting for their homes and their families, not merely waging a battle against the domino theory or to vindicate American capitalism against the challenge of atheistic communism.

Read the diaries of the soldiers who died in the Battle of Antietam or who stormed the beaches of Normandy. They were often preoccupied with concerns more parochial than abolition or the fight against fascism, as vital as both those struggles were. They invoked parents and wives, friends and neighborhoods, the farms they grew up on and the city streets they knew like the backs of their hands.

McCain himself is remembered not for his concise refutation of Marxist-Leninism or recitation of The Road to Serfdom. We praise him for his sacrifice on behalf of real people, for refusing to be released before his comrades in arms just as much as for what it meant to the lives of those men as for the propaganda victory he sought to deny the communists.

Unfortunately, the later period of McCain's career has been characterized by a low threshold for the use of military force and the advocacy of war on an unsustainably large number of fronts. That is another failing of his ideological approach to foreign policy: The excessive propensity to wage war is thought to be one of the failings of blood-and-soil nationalism. Yet it is plainly present in McCain's more idealistic version too.

McCain appeals to these abstractions as much to avoid debate as to engage in it. If you do not wish to intervene militarily in an area where the Arizona senator says we must, you "refuse the obligations of international leadership." If you wish to admit fewer immigrants for a certain period of time than would be permitted under a bill McCain sponsors, you "would rather find scapegoats than solve problems."

In theory, this more abstract view of America and its role in the world is more inclusive because it is not limited by race or ethnicity. In practice, it is often more exclusive when a diverse group of people who were either born in the United States or have lived here most of their lives fail to pass the requisite ideological litmus tests — thus becoming as "unpatriotic as an attachment to any other tired dogma of the past that Americans consigned to the ash heap of history."

So skepticism about the idea that it is more practical to guard Iraq's borders than America's belongs on the "ash heap of history" alongside Nazism and communism?

The debates this kind of talk suppresses are important, because our history includes not just sweeping victories on behalf of our ideals but also conflicts like World War I, Vietnam, and Iraq that many would judge to have been failed interventions that set back our fights against fascism, communism, or a variant of radical Islam armed with the tools of terror.

Interestingly, a younger senator who largely agrees McCain on foreign policy has taken a different approach. Sen. Tom Cotton (R-Ark.) delivered a speech of his own in Washington, D.C. balancing the American idea with the less abstract American homeland.

"Unlike any other country, America is an idea — but it is not only an idea," Cotton said. "America is a real, particular place with real borders and real, flesh-and-blood people. And the declaration tells us it was so from the very beginning."

Divorcing these two facts will give us immigration and foreign policies that don't work — and is increasingly delivering an illiberalism across the Western world that is at odds with what McCain is preaching.

Create an account with the same email registered to your subscription to unlock access.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

W. James Antle III is the politics editor of the Washington Examiner, the former editor of The American Conservative, and author of Devouring Freedom: Can Big Government Ever Be Stopped?.

-

Nigeria's worsening rate of maternal mortality

Nigeria's worsening rate of maternal mortalityUnder the radar Economic crisis is making hospitals unaffordable, with women increasingly not receiving the care they need

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

'Elevating Earth Day into a national holiday is not radical — it's practical'

'Elevating Earth Day into a national holiday is not radical — it's practical'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

By Harold Maass, The Week US Published

-

UAW scores historic win in South at VW plant

UAW scores historic win in South at VW plantSpeed Read Volkswagen workers in Tennessee have voted to join the United Auto Workers union

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

Arizona court reinstates 1864 abortion ban

Arizona court reinstates 1864 abortion banSpeed Read The law makes all abortions illegal in the state except to save the mother's life

By Rafi Schwartz, The Week US Published

-

Trump, billions richer, is selling Bibles

Trump, billions richer, is selling BiblesSpeed Read The former president is hawking a $60 "God Bless the USA Bible"

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

The debate about Biden's age and mental fitness

The debate about Biden's age and mental fitnessIn Depth Some critics argue Biden is too old to run again. Does the argument have merit?

By Grayson Quay Published

-

How would a second Trump presidency affect Britain?

How would a second Trump presidency affect Britain?Today's Big Question Re-election of Republican frontrunner could threaten UK security, warns former head of secret service

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

'Rwanda plan is less a deterrent and more a bluff'

'Rwanda plan is less a deterrent and more a bluff'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

By The Week UK Published

-

Henry Kissinger dies aged 100: a complicated legacy?

Henry Kissinger dies aged 100: a complicated legacy?Talking Point Top US diplomat and Nobel Peace Prize winner remembered as both foreign policy genius and war criminal

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Last updated

-

Trump’s rhetoric: a shift to 'straight-up Nazi talk'

Trump’s rhetoric: a shift to 'straight-up Nazi talk'Why everyone's talking about Would-be president's sinister language is backed by an incendiary policy agenda, say commentators

By The Week UK Published

-

More covfefe: is the world ready for a second Donald Trump presidency?

More covfefe: is the world ready for a second Donald Trump presidency?Today's Big Question Republican's re-election would be a 'nightmare' scenario for Europe, Ukraine and the West

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK Published