What Republicans miss about the dignity of work

Humans want dignity. They also want work. This doesn't mean all jobs are dignified.

Republicans have a new talking point. Over the next few months or years, expect to hear more from the right about "the dignity of work." It's part of a concerted effort to rebrand the GOP as a right-wing labor party. With unions in shambles and progressives at cultural loggerheads with America's working class, the Republicans are now poised to seize the mantle of Samuel Gompers and Cesar Chavez.

From an electoral perspective, this may be a good strategy for Republicans. By recasting itself as the new labor party, the GOP will likely lose some affluent middle-class voters, but it stands a chance of retaining the white working class and social conservatives, while also elevating its tone enough to attract at least a few others. That might be the best strategy available to a populist, Trumpian right.

Will a refocused Republican Party actually serve the interests of working Americans, though? That's a more difficult question.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Work is absolutely an important part of human life. In arguing for the dignity of work, though, Republicans tend to gloss over a crucial point. In order to be dignified, work must be useful. Sweat and tears win us dignity only if they contribute something of value to our society. This inconvenient reality places certain natural limits on what policymakers can do to generate dignified jobs for all who want them.

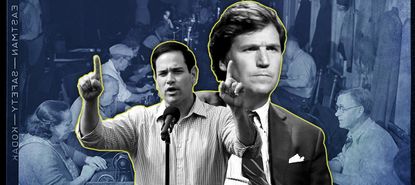

What gives work dignity, after all? Listening in on the right-wing conversation, you might get the idea that dignified jobs are primarily those that afford stability and decent wages, mostly likely without demanding that you uproot yourself from your community and way of life. In other words, dignified jobs are those that dovetail comfortably with the family and community goals that the right considers to be healthy. Thus, Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.) stressed in a recent essay that Americans need "stable jobs that pay enough to buy a home and raise a family." Tucker Carlson, in his recent broadside on America's financial system, suggested that elite obsession with GDP growth has robbed ordinary Americans (especially men) of the stable jobs they need to maintain strong families and communities. A more careful and responsible version of that argument can be found in Oren Cass' recent book, which advises policymakers to embrace a "productive pluralism" that tries to tailor our labor market to the community needs and lifestyle preferences of ordinary Americans.

This discourse draws out some important points, but it dodges the issue of usefulness by presenting us with a false dichotomy. If we really have to choose between "money-oriented" policy and "people-oriented" policy, or between a "consumption mentality" and a "production mentality," then the choice seems obvious, and the bleak alternative justifies any necessary sacrifices. In reality, there is no such choice to be made, because production and consumption are intimately connected. Cass and Carlson are of course correct when they assert that GDP growth isn't the only thing that matters. But no one, even a hard-boiled libertarian, would claim otherwise. The GDP is just one of many measures of a society's general thriving, but it is the most reliable measure of certain types of productive activity, especially those that are intrinsically focused on money or mass-produced material goods. Those kinds of jobs had better make a positive contribution to the national GDP. If they don't, they're not useful, and useless jobs are not dignified.

This point is easily obscured, for two reasons.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The first reason is that while people do need to work, jobs themselves are not self-justifying. Employment can yield many important benefits to workers — like discipline, sustenance, and, potentially, status as a valued member of society — but it does so precisely because it represents a meaningful contributions to society. If a person wants accolades for "work" that actually contributes nothing to his society (an incredible Pac-Man score, for instance), he's more pathetic than dignified. We shouldn't want our policymakers to distort reality deliberately, making unproductive activity appear useful.

The second reason is that some jobs do make social contributions that can’t be measured in money. If you're a schoolteacher, minister, or sidewalk artist, you may justifiably believe that your work has a value that isn't reflected in your paycheck. It's hard to put a dollar value on beauty, truth, or meaningful human relationships, and often the real beneficiaries of our labors simply aren't in a position to pay.

This point is important, but it doesn't help our right-wing labor theorists as much as you might suppose. They usually aren't pushing for more schoolteachers or sidewalk artists. Rather, they want to bolster trades, manufacturing, and other lines of work that seem appropriate for men lacking higher degrees. Many of those jobs are oriented around making standardized things. And it's fairly easy to put a dollar value on standardized things. Customers go to the butcher, baker, or candlestick-maker for a fairly simple reason: They want the goods that those people are selling. If possible, they'd prefer to get the same items for less money. When businessmen take steps (whether they're hiring goons or leaning on populist politicians) to deny customers that opportunity, they may be sabotaging their community more than they serve it. Is there dignity in demanding that your fellow citizens live darker and hungrier lives, so that you get to be the one to supply their bread and candles?

There are many more complications to this picture. Trade policy is tortuous even in relatively "free" markets, and regulations are often imposed for ambiguous purposes. Advertising and brand management may help people navigate a bewildering array of products, but they also shape desires in potentially-unhealthy ways. Then there are all the intricacies of taxes, patent laws, licensing agreements, and the like. Even for the most straightforward of products, no market will ever be perfectly efficient, so there will never be a precise point at which "genuinely productive labor" becomes a patronizing sham.

Complexity is not an excuse for dismissing the relevant principle, though. Capable adults should want to make real contributions to their society. This is an essential aspect of dignified work, and at least in some instances, there are fairly reliable ways of measuring whether or not a job is achieving that goal. If we allow policymakers to ignore those measures, we'll open the door to myriad forms of corruption and cronyism, as well as patronizing social-engineering projects that belittle the dignity of the very workers they claim to protect. We shouldn't want our policymakers to distort our economy out of a touching concern to ensure that men spend their weekdays at the office (or factory, or construction site).

America does indeed have a surfeit of unhappily-idle adults, especially men. We should want to help them if we can, and Cass and Rubio both have many suggestions along these lines, some of which may be good. Still, a healthy discussion of labor must never overlook the importance of the human desire to contribute and achieve. If we want to bolster the dignity of marginalized Americans, therein lies the answer.

Create an account with the same email registered to your subscription to unlock access.

Rachel Lu is a writer based in Roseville, Minnesota. Her work has appeared in many publications, including National Review, The American Conservative, America Magazine, and The Federalist. She previously worked as an academic philosopher, and is a Robert Novak Journalism Fellow.

-

The World War Two experiments that made D-Day possible

The World War Two experiments that made D-Day possibleUnder The Radar Scientists performed gruelling tests on themselves paving the way for the iconic invasion

By Chas Newkey-Burden, The Week UK Published

-

Is the Supreme Court about to criminalize homelessness?

Is the Supreme Court about to criminalize homelessness?Talking Points The court will decide if bans on outdoor camping are 'cruel and unusual'

By Joel Mathis, The Week US Published

-

Fall into the groove at these delightful record stores

Fall into the groove at these delightful record storesThe Week Recommends Each one strikes its own chord

By Catherine Garcia, The Week US Published

-

Arizona court reinstates 1864 abortion ban

Arizona court reinstates 1864 abortion banSpeed Read The law makes all abortions illegal in the state except to save the mother's life

By Rafi Schwartz, The Week US Published

-

Trump, billions richer, is selling Bibles

Trump, billions richer, is selling BiblesSpeed Read The former president is hawking a $60 "God Bless the USA Bible"

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

The debate about Biden's age and mental fitness

The debate about Biden's age and mental fitnessIn Depth Some critics argue Biden is too old to run again. Does the argument have merit?

By Grayson Quay Published

-

How would a second Trump presidency affect Britain?

How would a second Trump presidency affect Britain?Today's Big Question Re-election of Republican frontrunner could threaten UK security, warns former head of secret service

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

'Rwanda plan is less a deterrent and more a bluff'

'Rwanda plan is less a deterrent and more a bluff'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

By The Week UK Published

-

Henry Kissinger dies aged 100: a complicated legacy?

Henry Kissinger dies aged 100: a complicated legacy?Talking Point Top US diplomat and Nobel Peace Prize winner remembered as both foreign policy genius and war criminal

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Last updated

-

Trump’s rhetoric: a shift to 'straight-up Nazi talk'

Trump’s rhetoric: a shift to 'straight-up Nazi talk'Why everyone's talking about Would-be president's sinister language is backed by an incendiary policy agenda, say commentators

By The Week UK Published

-

More covfefe: is the world ready for a second Donald Trump presidency?

More covfefe: is the world ready for a second Donald Trump presidency?Today's Big Question Republican's re-election would be a 'nightmare' scenario for Europe, Ukraine and the West

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK Published