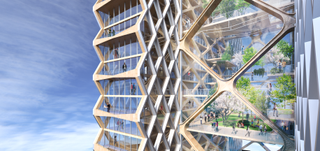

How to build a skyscraper out of wood

Wooden skyscrapers sound bizarre, unsafe, maybe even a bit twee. But they could actually be the future of construction.

Building skyscrapers out of wood: It sounds bizarre, unsafe, maybe even a bit twee. But it could actually be the future of construction.

"Each material has its different pros and cons, and there's no reason that timber shouldn't be part of that larger discussion," Todd Snapp, an architect with the global firm Perkins + Will, told The Week. "I can't say it's better than steel or concrete. I can say it should be just as relevant in the discussion of what material to use."

Snapp is the design principal guiding the firm's River Beech Tower project, an 800-foot residential skyscraper that would be built almost entirely out of wood. The tower was designed in parallel with a master plan the firm was awarded to develop an area in Chicago's downtown, on the east shore of the river and just west of Grant Park. Cambridge University's Natural Material Innovation project then came to them with the notion of doing a wooden skyscraper. The idea was they would pick a real-world site and then develop the building from the ground up: As the architects fleshed out the project, that would give the Cambridge group specific structures, practices, and so forth to test out in the lab. "We wanted the research to be tied to some sense of what's immediately achievable," Snapp explained. "Ground it in reality. Let's have a real site."

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Granted, River Beech Tower remains purely conceptual — a collection of designs and models, with no actual plans yet to build it. But the point of the project was to prove the idea could work.

Nor is it the only such effort. Similar plans are underway in London, Stockholm, and other cities. Eighteen-story buildings made of timber already exist in Vancouver and Minneapolis, while other structures have popped up in Norway and New Zealand.

Perkins + Will actually got its start in Chicago back in 1935. In fact, the city's great fire of 1871 was one of several disasters that helped push modern architecture away from wood and towards the steel and concrete that dominate construction today. Part of that legacy is Chicago's architecturally iconic Wrigley Building, which houses the offices where Snapp and his colleagues did much of their work on the River Beech Tower project. It's one of many efforts around the world to take history full circle and return timber to a place of prominence in architecture.

But why the effort in the first place? Well, several reasons.

For one thing, wood is lighter and more flexible than steel or concrete. A wooden skyscraper will have more give in an earthquake, for instance. The lighter weight also opens up opportunities for cost saving throughout the construction process. Wood is an excellent insulator, which would save the building's owners and residents on heating and cooling costs.

On the flip side, wood can sway too much, particularly in the wind — a major issue for taller buildings. For the River Beech Tower project, Snapp and his colleagues actually solved this problem by constructing the whole building out of triangle and diamond shapes. A triangle is a much more structurally sturdy form than a rectangle, so taking a more flexible material like wood and building triangles out of it created a structure that holds up well under forces coming at it from all sides. It also lent the project its interesting "honeycomb" aesthetic. Key connection points in the building would be reinforced with steel encased in concrete, and glass would be used in windows along with some other exterior materials. Beyond that, the skyscraper would be basically all wood.

Solving the flexibility vs. rigidity tradeoff lead to other interesting breakthroughs. The initial design of the project that Perkins + Will modeled in its computers was your standard skyscraper tower. The engineers determined the entire bottom third of the building would have to be a solid wood block to give the structure enough stability. So they redesigned the building as essentially two skyscrapers conjoined by a central atrium. That allowed them to spread the base of the building wide enough to get the necessary structural stability. It also gave them a big open space going up the core of the building, which opened up all sorts of aesthetic and interior design possibilities.

"We wanted the design to evolve out of the iterative process of what the material wants to be," as Snapp put it.

Another interesting aspect of wood is that it's easier to work with than steel or concrete. Concrete has to be poured into a preset form, then allowed the time — sometimes days or weeks — to dry. Steel has to be melted and molded into the necessary shapes. Wood, however, can simply be cut. Computers and modern technology now allow for factory processes that can cut timber into all sorts of desired shapes quickly and in large quantities.

That fact allowed the River Beech Tower team to get creative about the construction process as well as the design. They came up with a plan where the building would be constructed out of standardized modules, all prefabricated at a nearby factory, then shipped to the construction site. This modular approach is not unheard of in standard construction, but it's still relatively new, and the use of wood allowed the team to take full advantage of it. It's a strategy that can save you a lot of time. And building the modules under factory settings provides for more quality control than building the whole skyscraper on site from the ground up. How far this practice could spread depends on the circumstances of each building — having Lake Michigan right next to Chicago was a big help for shipping plans — but it certainly has possibilities.

Of course, any talk of building skyscrapers out of wood is immediately going to raise concerns about fires. (Remember the aforementioned Great Chicago Fire of 1871?) But wooden beams can be covered with fire-proof coatings, just as steel beams are. More importantly, the wooden beams created with modern processes are so big and solid that it actually takes enormously high temperatures to set them on fire — below those temperatures, the surface of the beam simply chars, while the beam itself maintains its structural integrity. "Steel is actually less fire resistant in its pure form," Snapp said. "When steel hits a certain temperature it starts melting, the connections break."

Finally, it's also worth mentioning that a world where we built a lot more skyscrapers out of wood would almost certainly be a more environmentally friendly place.

Obviously, there are aspects of construction that will emit CO2 no matter what material you use. But steel and concrete also have carbon emissions intrinsic to that material: Sixty percent of concrete's emissions, for instance, come from the chemical reaction to make the concrete. Replacing a lot of steel and concrete construction with wood could save us a lot of CO2 output.

On top of that, timber is a cash crop, just like corn or potatoes. If demand for it goes up, the economic incentive to plant more trees increases too. If wooden construction became common, you'd certainly need regulatory oversight to make sure the timber came from cash crop planting and not from cutting down pre-existing forests. But planting more trees is an excellent idea for fighting climate change.

So what's standing between us and our timber skyscraper future?

Mainly time, experience, and acceptance. Architects and engineers are only just beginning to realize the possibilities of bringing wood back into the equation, now that engineering technology has advanced. Governments and construction companies still need to get used to the idea. And building codes need to change: Right now the most widely used codes limit wooden construction to around 20 stories. But those codes are updated regularly, and projects like Perkins + Will's River Beech Tower feed into the process of reviewing and expanding what's allowed.

The field of wooden skyscrapers is young. But like the trees it relies upon, it may yet grow into something remarkable.

Create an account with the same email registered to your subscription to unlock access.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

'Make legal immigration a more plausible option'

'Make legal immigration a more plausible option'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

By Harold Maass, The Week US Published

-

LA-to-Las Vegas high-speed rail line breaks ground

LA-to-Las Vegas high-speed rail line breaks groundSpeed Read The railway will be ready as soon as 2028

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

Israel's military intelligence chief resigns

Israel's military intelligence chief resignsSpeed Read Maj. Gen. Aharon Haliva is the first leader to quit for failing to prevent the Hamas attack in October

By Justin Klawans, The Week US Published

-

The pros and cons of noncompete agreements

The pros and cons of noncompete agreementsThe Explainer The FTC wants to ban companies from binding their employees with noncompete agreements. Who would this benefit, and who would it hurt?

By Peter Weber Published

-

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contraction

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contractionThe Explainer The sharpest opinions on the debate from around the web

By Brendan Morrow Published

-

The death of cities was greatly exaggerated

The death of cities was greatly exaggeratedThe Explainer Why the pandemic predictions about urban flight were wrong

By David Faris Published

-

The housing crisis is here

The housing crisis is hereThe Explainer As the pandemic takes its toll, renters face eviction even as buyers are bidding higher

By The Week Staff Published

-

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkers

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkersThe Explainer Show up for your colleagues by showing that you see them and their struggles

By Tonya Russell Published

-

What the stock market knows

What the stock market knowsThe Explainer Publicly traded companies are going to wallop small businesses

By Noah Millman Published

-

Can the government save small businesses?

Can the government save small businesses?The Explainer Many are fighting for a fair share of the coronavirus rescue package

By The Week Staff Published

-

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shock

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shockThe Explainer This could be a huge problem for the entire economy

By Jeff Spross Published